‘When you do something, you should burn yourself up completely, like a good bonfire, leaving no trace of yourself.’ ~Shunryu Suzuki-roshi

The immediacy, even intimacy, of cooking over a campfire adds layers of warmth to any meal. Outdoor firepit cooking requires thoughtful consideration to the preparation of the fire and the food, as well as a level of attentiveness during cooking, that demands mindfulness. There is a Zen to being consumed in the task.

On a recent trip to the lake in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, we endeavored to cook all of our meals on the campfire. A discussion ensued about several past dishes we had made and this post will be a quick rundown of those dishes and the different campfire techniques we have used. One of our actual meals, The Ultimate Patty Melt, will be a subsequent post.

The Fire

First things first – the fire. We prefer to cook over a stone lined pit with primarily hardwoods for fuel. By digging the pit down and lining with stones, we contain heat and avoid some of the effects of wind, which can cause flare-ups or excessively hot fires. We don’t go as far as the Dakota Fire Hole approach, but we may at some point.

Use hardwoods like oak, birch, or maple. If you have access to fruitwoods, like apple or cherry, those are nice to mix in as well. Unfortunately, we had to take down a 80 year-old apple tree that had died a few years ago. Fortunately, we’re still working through the wood supply. Avoid pine, as it tends to release a acrid, bitter black smoke. Simple technique to determine if the wood is suitable for cooking – cup your hand well above the fire and pull smoke to you to smell. If it is plesantly smokey or even a bit fruity, you’re all set. If the smoke is bitter, consider other wood options.

The Approaches

Part of the beauty of campfire cooking is the ability to use no tools at all. Just the right stick can be all you need. But if we’re going to get a bit more complex with our preparation, a couple simple tools help. We like to use a simple sheet of expanded metal to create a working base.

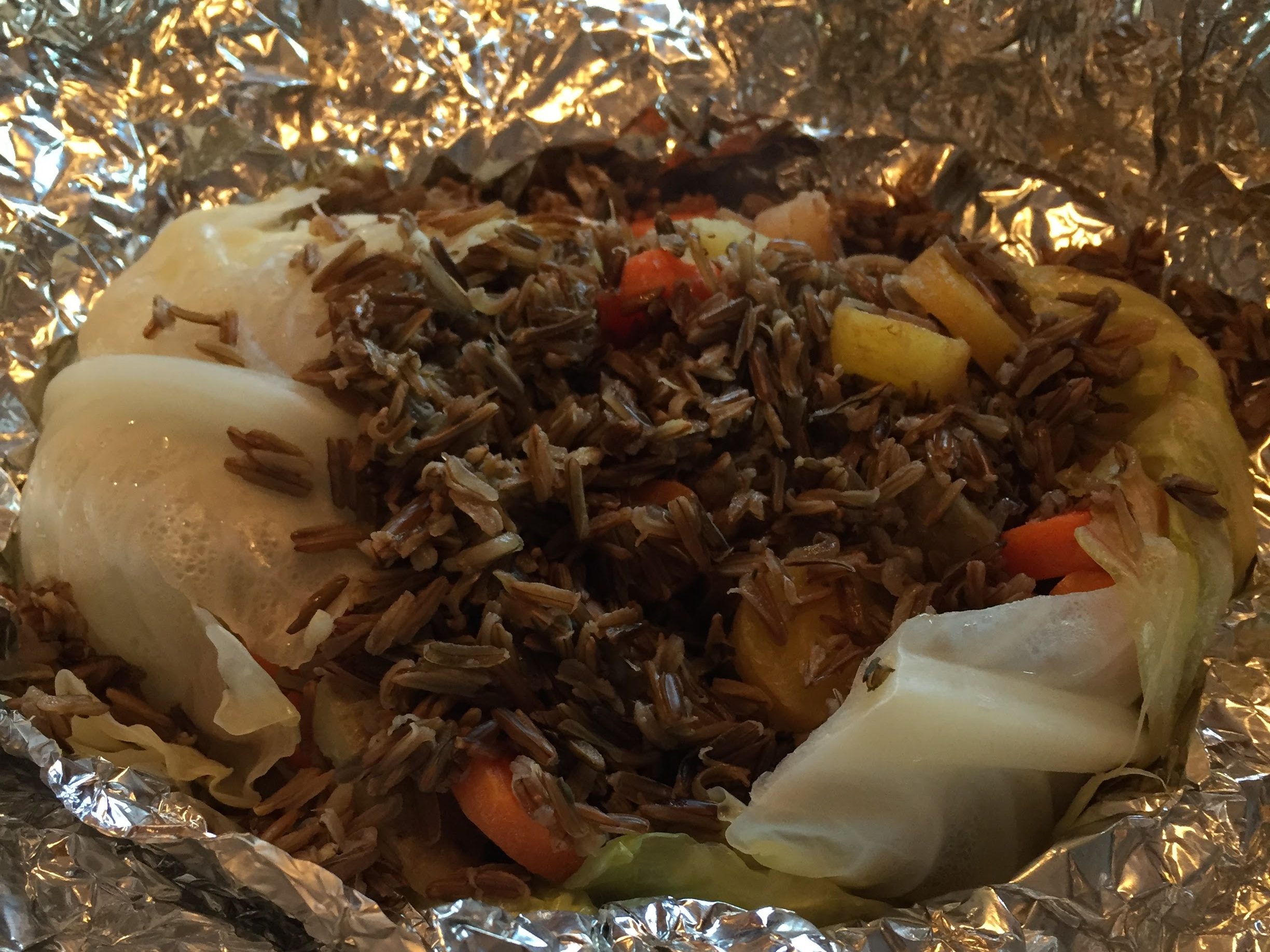

Here we are making Tin Dins – “tin-foil” wrapped dinners. In the camp tradition in our family these typically include multiple cabbage leaves as a base, then onions and par-cooked potatoes with a good knob of butter, topped with a protein (like a hamburger patty or a piece of 8-cut. bone-in, skin-on chicken) and wrapped in aluminum foil.

Here we went with a wild rice along with onions, carrots, and potatoes to create almost a campfire, fried rice effect. The foil seals in steam to cook the package faster. The cabbage provides liquid that converts to steam, a bit of flavor, and a buffer against charring the food. Most often the bottom leaf or two of the cabbage remains uneaten as it is often charred to the foil. Par-cooking the potatoes can be done a few ways – place them in the cooling embers of last night’s fire, pre-boil them until just softening over the campfire in a pot, or simply boil them stove-top prior to the camping trip and keep them cool along with the protein of choice. Cook time is more art then science (more accurately it’s 100% science, but it’s hard to know exactly when they are done without piercing the foil wrapper) but you get a pretty good feel for it over time. Don’t hesitate to go more “low and slow” on the heat rather than trying to rush it.

Another tool we like a lot is a heavy cast iron pan. Above is the the Lodge Dutch Oven that has become our go-to camp pan, though we have used a variety of other cast iron pans in the past. Warning: Once a cast-iron pan becomes a campfire pan, it is pretty much gone wild. It is very hard to clean the accumulated smoke off the outside in order to domesticate that pan once again for indoor use.

Ensure your cast iron pan is really well-seasoned. If you need help, Lodge has a helpful article here. We seasoned ours a bit longer than recommended on the gas grill prior to the campfire use in order to ensure a really good, near non-stick base coating. We still use a healthy amount of butter or oil when cooking potatoes or eggs.

The cast iron is thick enough to spread the heat of a campfire fairly evenly across the bottom of the pan and the heavy lid on the Dutch oven allows foods to cook off the fire. We often pre-cook the breakfast sausage in the pan, then remove, and follow them with the potatoes and onions. When the potatoes are soft, we add back the diced (or whole) sausage, then remove the pan from the fire and add the eggs, allowing them to cook in the residual pan heat with the cover on.

We detailed our approach to whitefish over the fire, and all the attendant memories that dish spawned, in this previous post. Another great use for the Dutch oven is for overnight roasting, which we did for our fire-roasted butternut squash feature in this post.

We’ve also done the occasional dessert over the fire, with our favorite being Michigan peaches, cooked in butter and brown sugar. Get these going over low coals, or elevate the grate well above the fire. Sugar burns easily and can get blistering hot. Just as the peaches soften and the sugar is fully caramelized, pull from the fire and allow to cool until warm to the touch. Then top each serving with a healthy dollop of Driftless Honey & Lavender from Hidden Springs Creamery, and drizzle of the caramelized juices from the pan.

We also have accumulated any number of specialty campfire cooking over the years, from simple metal marshmallow roasting sticks to an absurd hotdog rotisserie tool (because apparently turning it on a stick was too much work?). And though Alton Brown is right about single-use cooking tools, we do love the campfire pie iron. We have done grilled cheese, peanut butter sandwiches, marshmallow and chocolate pockets, and of course, apple and cherry hand pies. So I guess it really isn’t just “single-use” after all. Butter your bread well before placing it it butter side down in the lower pie iron, then fill and top with another piece of bread, butter side up. Crimp tight, trim the edges and toast away on the fire. Allow it to cool slightly before enjoying.

Any recipe can be adapted to the fire with some thought and preparation. And some of the world’s most iconic dishes are really only properly prepared over a fire, think paella or booyah. Fire cooking can be a demanding, and that is part of what we love about the process – it demands your appreciation for the fire and attentiveness to your actions. This isn’t simply prepare a recipe and stick it the oven or throw it in a pan. Sure, we love the smokey tones in each dish we make over the fire, but it is the attention to what we are doing, being in the moment of cooking that provides a bit of Zen. And sitting beside a lake, enjoying a cold brew, and digging into a hot camp fire meal is definitely part of what Great Lakes Cuisine is all about.

One thought on “Lakeside Campfire Cooking”